Even after losing both of his legs following a combat injury, enduring 28 surgeries and spending nearly two months in the hospital, the physical toll wasn’t the most difficult thing Temo Dadiani ’24G recalls battling.

It was the inaction.

Dadiani, a native of the Republic of Georgia in Eastern Europe, was 19 years old and serving his country as a soldier when he stepped on an IED during a joint mission with the U.S. Marine Corps in Afghanistan in 2011. The blast cost him both legs and the pinky finger on his right hand, and the ensuing medical procedures and rehab were grueling.

But it wasn’t until he returned home, to a country ill-equipped to provide support for people in his condition, that the darkest hours truly set in. Dadiani, incredibly driven and energetic by nature, struggled in stillness.

“That was a time when I was figuring out how to continue my life. In my country, nobody offers programs for people with disabilities. I was just staying home and doing nothing – just completely nothing,” Dadiani says. “That was for about eight months, and I was just trying to keep myself motivated somehow.”

He received the lifeline he needed when the United States and Georgia partnered to get him to the Naval Medical Center in San Diego, where he was able to utilize state-of-the-art rehab facilities and work with other wounded soldiers with prosthetics – an experience that wholly reignited him.

Now, as he wraps up a master’s degree in adaptive sports at UNH, Dadiani – fueled by his own experiences and the skills and knowledge he’s gained as a graduate student – is committing himself fully to changing the landscape in his native Georgia so others in similar positions can find the support they need close to home.

“This is why I decided to get an education in adaptive sports – when I go back, I want to help my country start programs for people with disabilities,” Dadiani says. “The program at UNH has given me the opportunity to improve my knowledge and to take this experience to my country and share it with my people. They are waiting for me – they are saying, ‘We are going to do something together, you’re going to start something new, and you are going to change lives here.’”

Dadiani’s is a story of unrelenting grit and remarkable selflessness in the face of personal adversity. Even his journey to UNH featured various twists and turns and required more patience and persistence than anyone expected.

When Dadiani decided he wanted to pursue an education in adaptive sports, he wanted a place that offered three things – a master’s degree in the field, opportunities to participate in adaptive sports, and a chance to play sled hockey, in particular.

UNH was uniquely suited to check all three boxes, thanks in large part to Northeast Passage, a program focused on therapeutic recreation and adaptive sports as a means to empower people living with disabling conditions.

Dadiani, with help from a friend at the Naval Medical Center, settled on UNH as his preferred option in 2020. But the pandemic made already challenging travel logistics even more substantial, and because of that and other hurdles, Dadiani ultimately didn’t arrive until the fall 2022 semester.

He praises Jill Gravink, founder and executive director of Northeast Passage (NEP), and Patricia Craig, associate professor and associate department chair in recreation management and policy, for their tireless work in getting him to UNH, and Craig also credits the UNH Office for International Students and Scholars (OISS) with a massive assist in completing the process, as well.

Once Dadiani arrived, though, it didn’t take long for him to leave his mark. He’s been a standout student and has worked with NEP in a variety of ways since coming to the U.S., all with a focus on bringing what he’s learned back to Georgia with him.

“He’s just embracing this experience and getting every ounce he can out of it,” says Gravink. “He’s been very clear on his vision since he got here – that ‘I want to do this for my fellow soldiers, I want this for the kids of Georgia.’ He is like a sponge in absorbing things, focused on ‘How do I change the perception of disability within my country?’ He just continues to impress.”

"He’s so resilient, and he works through so many things so gracefully – so many barriers and challenges."

Despite his efforts, there will still be significant challenges ahead of him when he returns to Georgia. There is little existing infrastructure in the country for assisting those with disabilities, and Georgia doesn’t currently have access to the remarkable breadth of equipment Dadiani has been exposed to at NEP.

But despite that, nobody at UNH is planning to bet against him.

“Georgia is just starting in this area, and when he goes home, we’ve talked about how it will be challenging, because he won’t necessarily have the same resources he’s had in the states,” says Craig, who has served as Dadiani’s academic advisor. “But he’s so resilient, and he works through so many things so gracefully – so many barriers and challenges.”

Indeed, it’s easy to see how Dadiani has earned such faith from others. He tends to achieve what he sets his mind to, as evidenced by the list of sports he’s taken up and mastered since his injury – including hand cycling, archery, arm wrestling, powerlifting, swimming, Nordic skiing, downhill skiing, wheelchair fencing, lacrosse, shot put and the 100-meter run. He’s represented Georgia in Nordic skiing at the last two Paralympic Games, is a two-time Guinness World Record holder in planche pushups and is a two-time world champion in arm wrestling.

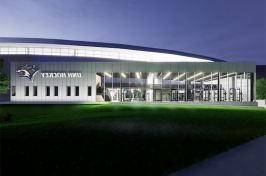

The latest addition to that list is sled hockey, which Dadiani first watched while at the Paralympic Games. He decided in that moment he wanted to play the sport himself, and UNH’s accomplished program – which regularly feeds players to the US national team that has won four consecutive gold medals at the Paralympic Winter Games – was certainly a draw. He has since joined the team and impressed, earning the nickname “The Georgian Rocket” from teammates, Gravink says.

That opportunity, in conjunction with RMP courses that have provided invaluable knowledge tied directly to his goal and the opportunities he’s had to work with state-of-the-art adaptive sports equipment at NEP have made Dadiani’s UNH experience a distinctive and fulfilling one.

“We had the academic piece, we had the practical experience and he’s been able to be an athlete, and that is very unique to the University of New Hampshire that we were able to provide all of those pieces for him,” Gravink says.

Now it’s Dadiani who is looking to provide those same pieces for those in his homeland. He is grateful for all the support he has received at UNH – he described Craig, Gravink and his professors as “amazing” and says he’s had an “incredibly positive experience” – and is excited to get home and officially start his work.

“I feel very satisfied for myself, but now I need to help the people in my country who don’t have the same opportunities I’ve had,” Dadiani says. “All I am thinking about is helping others, because I know when I saw fellow soldiers in the San Diego hospital, that’s when my eyes first became wide open – they gave me examples of how to live after something like this, and now I am in the same shoes, where I can give the same opportunities, the same examples to my people back in my country.”

-

Written By:

Keith Testa | UNH Marketing | keith.testa@runkennebec.com